Habitat

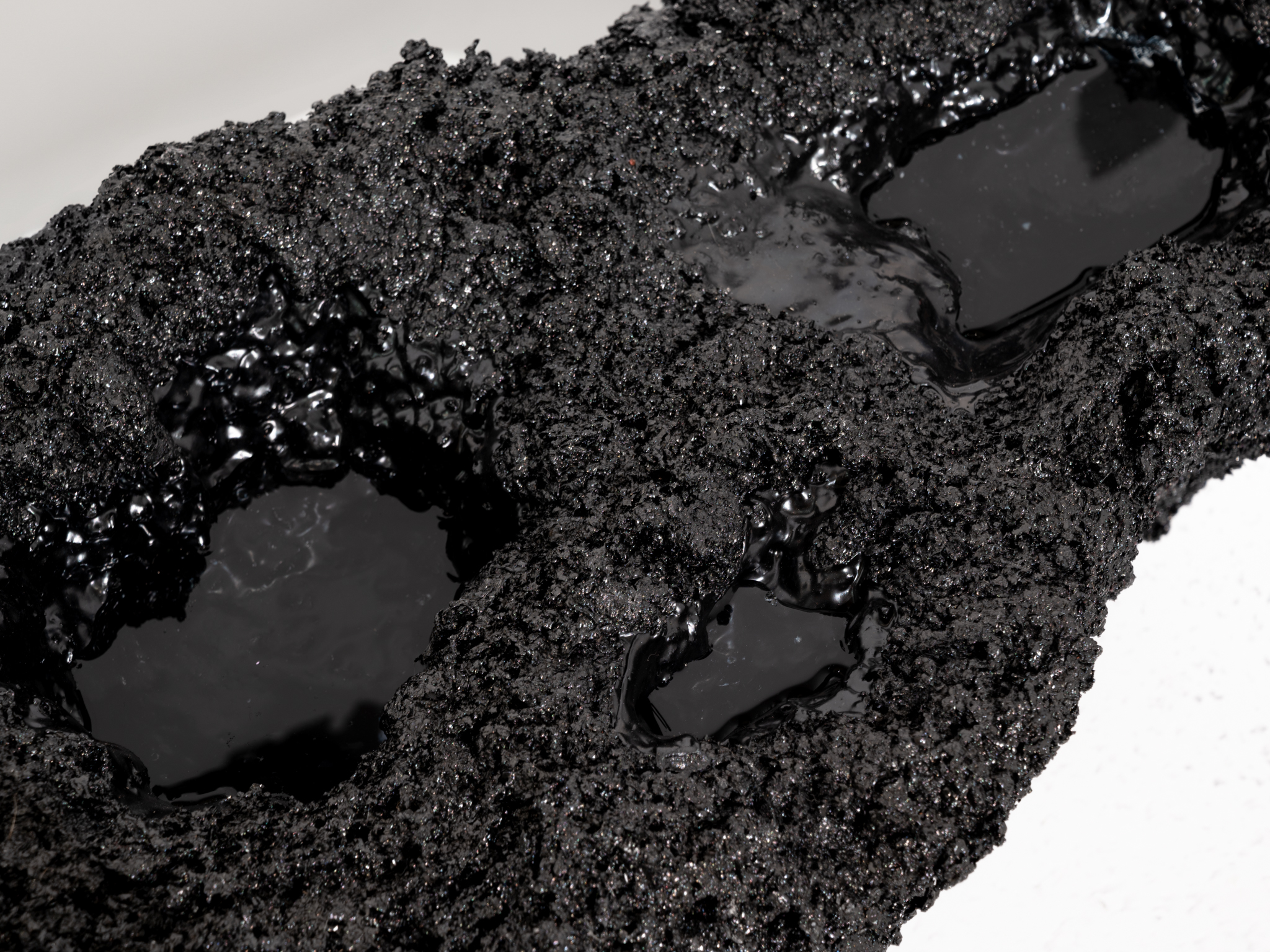

The project is an investigation into rosin as a binder combining carbon-negative biochar, derived from biogenic residues through pyrolysis, to develop a new thermoplastic material.

Forests are the context of one of the most complex ecosystems on earth. Over millions of years, plants, fungi, lichens, micro-organisms and animals have developed into a perfect biocoenosis that exists in mutual interaction and dependence. It is hard to imagine that the visible tree population of a forest represents only about half of the total biomass of these plants. The other half of the trees and shrubs live underground in root form. The building blocks of the forest mature cyclically, similar to natural resins, sticky tar or flexible fibres. This complex ecosystem, whose interactions we still do not fully understand, is the context of destruction and renewal, of rituals and traditions, of growth and decay, as well as of history and the future. The fragile yet robust future of the forest opens up spaces for new synergies between human and non-human actors.

Since ancient times, the Mediterranean forests have provided people with a diverse habitat and numerous goods. Rosin was a precious resource in Portuguese culture - the ‘tear of the gods’ - and played a crucial role in global trade relations, cultural developments and the country's wealth.

Since ancient times, the Mediterranean forests have provided people with a diverse habitat and numerous goods. Rosin was a precious resource in Portuguese culture - the ‘tear of the gods’ - and played a crucial role in global trade relations, cultural developments and the country's wealth.

Project development within the residency programme “Sustainability by Design (SBYD.SPACE)” initiated by Folkwang University of the Arts. The project was also supported by Prorresina, Produtos Resinosos LDA, Portugal.

Natural resins are amorphous, solid or highly viscous mixtures of complex, high-molecular substances, usually of plant origin. Natural resins are colloids (Greek kólla - glue and eidos - form, appearance) that form the liquid solvent turpentine in a mixture of various volatile compounds called terpenes and non-liquid solid compounds.

For centuries, natural resins were a precious resource in all cultures - the tears of the gods - were responsible for worldwide trade relations, cultural development and wealth. The human fascination for these malleable substances can be dated back centuries before Christ. They are closely associated with mythical tales, beliefs and rituals that cross all countries and cultures. These sunlight made materials filled the warehouses of early advanced civilizations in the form of small artfully shaped objects and trinkets. Where resins were traded, they also served as currency. Natural resins such as rosin, copal and shellac are among the oldest plastic moldable and thus renewable polymers used by humans. The Minoans, Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans used resins to seal their wooden ships. They made wood and fabric hydrophobic and created a surface that prevented the development of bacteria and decay.

For centuries, natural resins were a precious resource in all cultures - the tears of the gods - were responsible for worldwide trade relations, cultural development and wealth. The human fascination for these malleable substances can be dated back centuries before Christ. They are closely associated with mythical tales, beliefs and rituals that cross all countries and cultures. These sunlight made materials filled the warehouses of early advanced civilizations in the form of small artfully shaped objects and trinkets. Where resins were traded, they also served as currency. Natural resins such as rosin, copal and shellac are among the oldest plastic moldable and thus renewable polymers used by humans. The Minoans, Phoenicians, Greeks and Romans used resins to seal their wooden ships. They made wood and fabric hydrophobic and created a surface that prevented the development of bacteria and decay.

Resin tapping is a technique in which the bark of a pine tree is removed

from one third of its circumference, after which the resin that the

tree produces in that part can be harvested by means of incisions in its

outer layers. The resin can be harvested cyclical from May till October, without it

being a threat to the tree. When a tree has reached a trunk diameter of 20 cm, it can be tapped for a period of 20-30 years. A cut produces an average of 1 1⁄2 litres of resin per year. Today only a few small

production centres are still in existence, harvesting the resin with

traditional and artisanal techniques.

Today, resin tapping seems more relevant than ever. Environmental and social aspects take centre stage, as the intensity and frequency of forest fires is increasing, especially in Portugal. On the one hand, the risk of forest fires is reduced as is of great interest to the immediate communities to protect their trees, furthermore biodiversity is preserved and the rural economy is promoted.

In the region of Góis only one resin distillery remained. Amilcar Aleixo is now the third generation of his family to run the 100-year-old distillery Prorresina - Produto Resinosos, LDA in Chã de Alvares. The factory is relatively small, but nevertheless an architectural maze in several stages, built up according to the individual steps of the production process.

Rosin is made from the solid components of tree resin, which is obtained from the balsam of pines or spruces (conifers). It consists of approx. 70% resin, 20% turpentine and 10% water. After cleaning the raw pine resin, the mixture of turpentine oil and resin is distilled to separate the two substances. During this process, both the turpentine and the rosin condense. The rosin obtained in this way has a golden yellow colour. Traditionally, the rosin was heated in a large closed kettle with a condensation coil over an open fire, similar to a whisky distillery. After the turpentine and rosin are separated, the liquid rosin is poured into large metal vats, where it cools and hardens to an almost crystal clear colour.

The name rosin (also called colophony or Greek pitch / Latin: pix graeca) is derived from the name of the Lydian city of Colophon, which was an important trading centre for rosin in ancient times. Pine resin long characterised trade between Europe and the Middle East during the Greco-Roman period. The Greeks and Romans used the resin from various regions of France and Italy. As early as the 1st century, Dioscorides provided detailed information on pine resin from northern Italy. In ancient Greece, clay amphorae were lined with the resin to seal the surface. The typical flavour of Greek retsina is still produced today by adding Aleppo pine resin. In the seventh century BC, the resin was used in war as a liquid fire, the so-called Greek fire. It protected objects and surfaces from decay, bonded materials and was a versatile raw material that played a central role in everyday life and crafts in many cultures. Due to its antiseptic properties, it was also used as a remedy for the treatment of wounds and respiratory diseases. Before oil-based chemicals made

it redundant, it was a widespread industry all over Europe, since the

pine resin could be used for plenty of applications after distillation,

from pharmaceutics to cosmetics, in tar, but also in pre-industrialised plastics in the 19th century and

paint. It used to be an important component of linoleum, based on a mixture of linseed oil, cork flour, sawdust and colophony rolled onto a layer of jute, that was largely replaced by the plastic polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Today, pine resin is used on a much smaller scale as a sustainable source for a variety of products used in different industries such as chemicals, pharmaceuticals, food additives and biofuels.

All living tissue is made up of (organic) carbon compounds. Carbon is one of the most essential elements of the biosphere. Together with oxygen and water, it forms the skeleton of all life. In biochar production, biogenic residues such as green waste, pomace or manure are pyrolysed in a low-oxygen environment. Pyrolysis means not burning the biomass, but slowly decomposing the organic molecules into the purest possible carbon at temperatures above 350 degrees and just below the combustion point in the partial absence of air. In this way, complete combustion is prevented and the carbon of the biomass can be stably bound in the resulting material for several hundred years and beyond, which prevents the carbon from being released into the atmosphere during the natural decomposition of the biomass. Pyrolysis can also be used in the utilisation of residual materials. For example, residues from biogas plants, press residues from sunflower, rapeseed or olive oil production and fermentation residues from bioethanol production can be utilised. The energy for combustion comes from the combustion process itself; there is even more energy available, which can be used for further utilisation such as drying, heating or the production of electricity.

Can we cultivate a practice of care

through the material itself to develop

new modes of co-existence and promote a more sustainable and liveable

co-existence?

The project focuses on the agency of the material itself, providing objects that enable new modes of co-existence and interactions with other species to promote a more sustainable and liveable future. The objects the material have become show the explored qualities in plasticity and crusty surfaces.

The material is condensed, but not unchangeable. The objects have tendencies that are inherent to living systems: the ability to change, to decay and to return to nature as nutrients. The objects have been made in a self-defined and so called break- and-remake process. Due to the materials properties, each object can be melted again and transformed once more into another shape.

The material is condensed, but not unchangeable. The objects have tendencies that are inherent to living systems: the ability to change, to decay and to return to nature as nutrients. The objects have been made in a self-defined and so called break- and-remake process. Due to the materials properties, each object can be melted again and transformed once more into another shape.